This is Part III in a blog series about the Center’s Guidelines for Inclusive and Conscientious Description. Read Part I and Part II.

Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia's (A4BLIP) "Anti-Racist Description Resources" served as a springboard for us to address the issue of glorifying collection creators in archival description. A4BLIP pointed out that when archivists glorify white male creators, we exaggerate the power dynamic in archives. We wanted to fix finding aids that glorified creators without providing context. After creating the Guidelines for Conscientious and Inclusive Description, we audited our finding aids for compliance with the guidelines. We noticed many cases where important contextual information was missing. Biographical Notes sometimes sounded like eulogies, lacking balance. In some cases, we were aware of ethically-questionable activities a person had undertaken that had been excluded from the finding aid.

Many of our collections consist of records of people who contributed to their fields of medical research or clinical practice. Some developed treatments that changed the course of medical care. Many performed lifesaving humanitarian work. Others mentored trainees, pioneered treatments, or worked with underserved patients. However, we were aware that some physicians in our collections had performed unethical research, either by today’s standards or, in some cases, by the standards of their own time. Others had held dehumanizing beliefs about certain classes of people. This unsavory information was sometimes omitted from the finding aids that describe these people and their work. In other cases, the information was included, but without appropriate context. Our goal was to let a description of someone's work speak for itself. That would tell a researcher more than labels like a “larger-than-life figure” or a “fine human being,” as some of our finding aids did.

In this post, I’ll provide a few examples where missing information distorted the legacy of a collection creator, and I'll show how we modified the description to correspond with our new guidelines. Some of the new guidelines we followed during this process included:

“Avoid venerating creators or using superlative language, especially based on family relationships or reputation (A4BLIP, Drake, Bolding3). Recognize that neutrality in archival description is an unhelpful myth; at the same time, strive to avoid value judgments and leave interpretation to the researcher (A4BLIP, Berry, Robinson-Sweet, and others). This does not mean you cannot convey the impact of someone’s work – this can be important for contextualizing the records - but this should be done with a “show, don’t tell” approach; in other words, you should illustrate that impact by describing the work and the results of the work. You may also consider quoting from or citing biographical sources to convey impact or significance (example: “...often referred to as the ‘godmother of neonatology’ [citation]”), or rely on listing honors or awards received as a way to demonstrate recognition.”

“Pertinent information about the creator may include information that does not reflect positively on the person (Robinson-Sweet). Whenever possible, cite the source(s) of the information or point to the records that underpin the statement. State this information clearly.”

“Use language that neither glorifies a dominant group nor hides or misrepresents members of a marginalized group (A4BLIP).”

Please visit the Guidelines for Conscientious and Inclusive Description to see the sources cited.

Clemens Benda

Clemens Benda was a psychiatrist who studied intellectual disabilities. He directed several Massachusetts state hospitals from the 1930s through the 1960s. In one study at the Walter E. Fernald State School, in Waltham, Massachusetts, he collaborated with MIT and the Quaker Oats Company to study the nutrients in oatmeal. The study involved feeding students in state custody oatmeal that contained radioactive tracers. Today's basic standards of research ethics, particularly informed consent, were later established in the 1974 Belmont Report. In the 1990s, former Fernald students learned about the study in which they had participated decades earlier. They filed a lawsuit and received settlements. This unethical saga had been omitted from Benda's Biographical Note. In the updated Clemens Benda finding aid, we described the study, as well as the former-student activism: “In the early 1990s, former “Science Club” participant Fred Boyce learned about the radiation studies and worked with fellow students to take legal action and to publicize the abuses that occurred at Fernald (8).” (To see the biographical note click on “Additional Description.” You’ll also see the citations for the numbered footnotes). We also found that “Benda also studied hormone treatments for students with Down syndrome (he believed that “feeble-mindedness" was caused by problems in the glands), and he collaborated with Max Rinkel (1894-1966) on lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) studies that involved inducing psychosis in participants (9).” Researching Benda and reading about the troubling history of the Fernald School allowed us to reapproach the finding aid with more perspective. In this case, we had enough information to add an entire paragraph about Benda’s research.

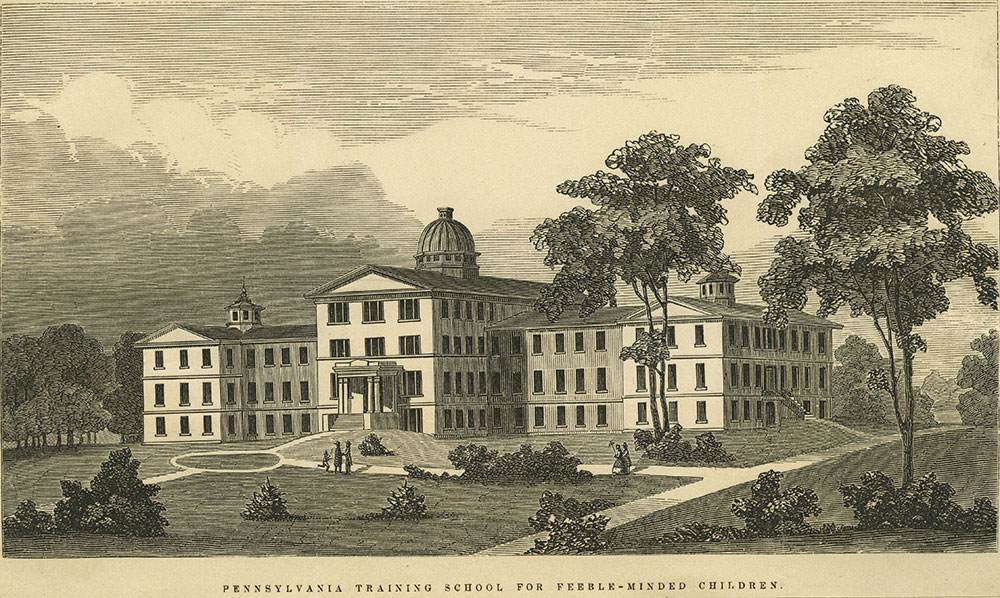

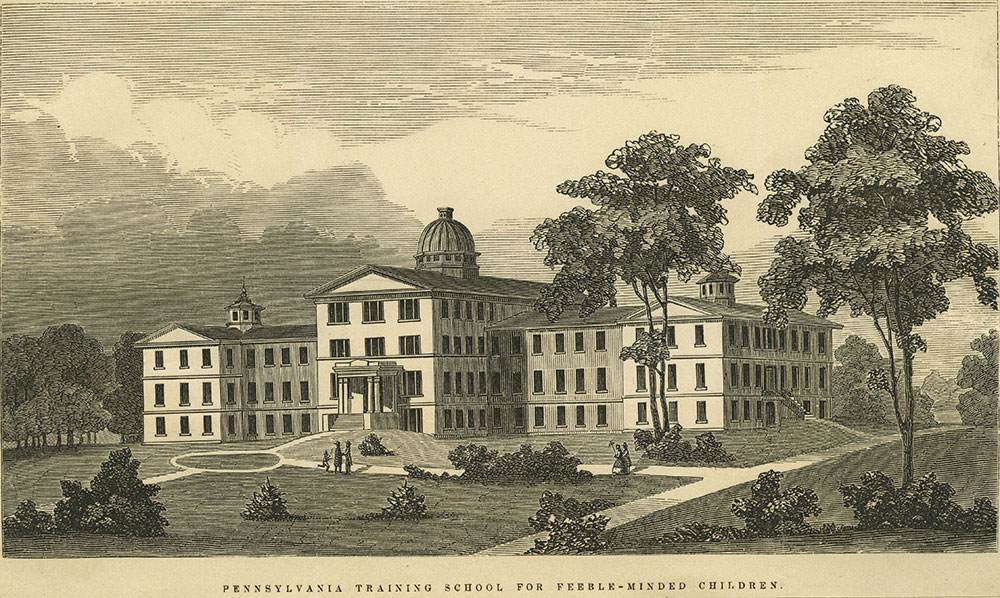

Isaac Newton Kerlin

Unlike the Benda finding aid, the Isaac Newton Kerlin finding aid did not completely omit unfavorable information about Kerlin’s work. Kerlin was Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children in Elwyn from 1863 to 1893. His Biographical Note described sterilizations of students with disabilities at the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children (now called Elwyn). However, this unsettling detail was framed in a relatively positive light. It was described using passive voice: “All sterilizations of patients at Elwyn were performed with the consent of the parents” (emphasis added). This framing made it seem like the Elwyn sterilizations were morally good compared with sterilizations for which parents did not give consent. This left me with questions about the sterilizations. Why were they performed? Who authorized them? Was this an example of negative eugenics, restricting people deemed "unfit" from reproducing? Or was it supposedly therapeutic? I researched the practice of sterilization at mental institutions so that I could add information to the finding aid. Now, the description explains why Kerlin supported sterilization. “Under [Kerlin’s] leadership, some students whose parents consented were sterilized; this was to control sexual behavior and to control epileptic symptoms.” This statement was accompanied by a citation to the Encyclopedia of Disability, edited by Gary L. Albrecht. The new description assigns agency for the sterilizations to Kerlin. It avoids praising Kerlin by the standards of nineteenth-century norms. It also avoids condemning Kerlin under twenty-first century morals. It simply provides contextual information.

Norman Himes

Another finding aid describes the papers of Norman Himes, a eugenicist. The finding aid described Himes’ study of “population problems; history of contraception and the birth control movement; marriage and family relations.” When I explored this, I learned that Himes believed that some classes of people were inferior to others and that these people, he believed, should not reproduce. The new description adds more context about Himes' work. It cites a 1938 New York Times article that discusses his eugenic beliefs. The finding aid now reads: “Himes’ areas of study included marriage, birth control, and population control. He believed that poor and disadvantaged people constituted the “wrong family stocks,” and that by reproducing, they were lowering the intelligence of the population.”

These examples show how simple changes can impact how a researcher might think about a collection creator. It just takes a little research to be able to describe a creator's work without resorting to accolades and laudatory statements, or omitting information about unethical activities. Our job as archivists is to provide context for researchers which sometimes means looking unpleasant information in the eye and describing it frankly.

We invite your feedback on our guidelines and on our updated finding aids, via email.