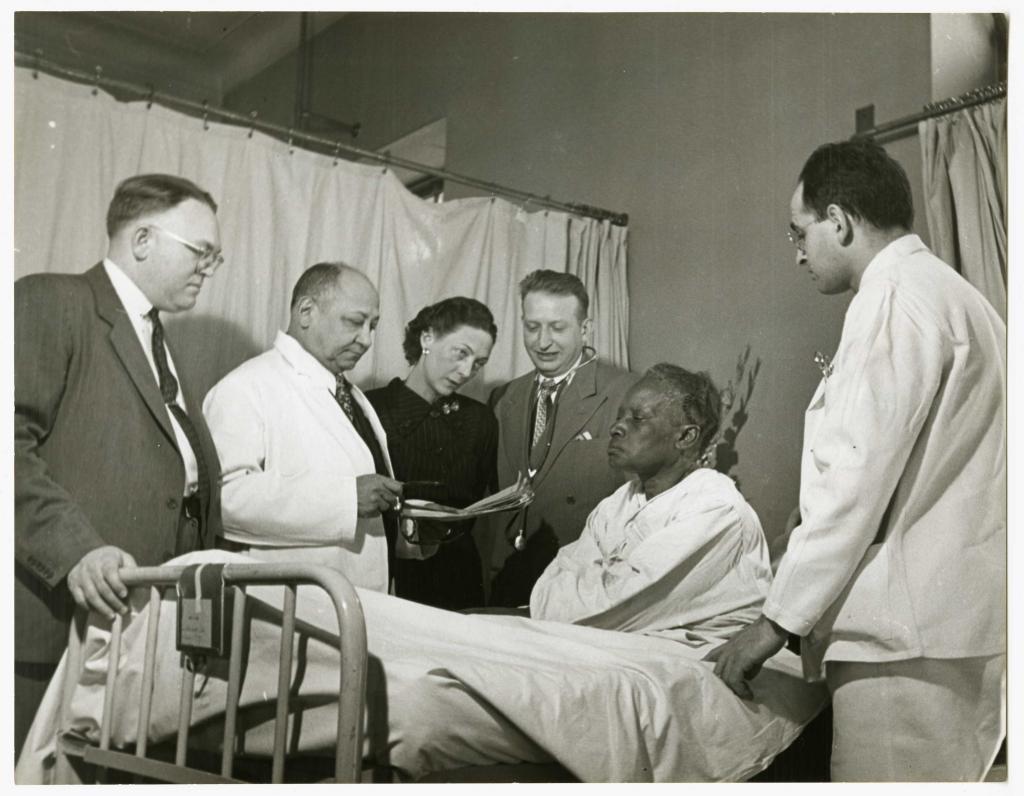

Covello, Joe (for Black Star)., “Louis T. Wright and colleagues at patient bedside, Harlem Hospital, New York, N.Y.,” OnView: Digital Collections & Exhibits, accessed November 24, 2020.

Over the past year, Center staff created a new archival description policy, Guidelines for Inclusive and Conscientious Description. One of the first areas we focused on was how we identify and describe the creators of archival collections. Our first goal was to ensure that we were using respectful language to describe people’s identities. We also recognized the importance of being transparent about creators' race. Describing collection creators conscientiously and completely provides important context for their life and work.

A poster created by Michelle Caswell and her students (with design by Gracen Brilmyer), got us thinking about what we, as white archivists, take for granted in description. The poster, "Identifying and Dismantling White Supremacy in Archives (PDF)," provides examples that illustrate archival white privilege. One says, “When I look for materials from my community in archives, they will be described in the finding aid and catalog record using language we use to describe ourselves.” This is often untrue for members of marginalized groups. Instead, they often reckon with outdated, offensive, or inaccurate terminology.

Using a collection creator's preferred language is a sign of respect. It also helps us avoid assumptions and imprecise language about that person's identity. Working with our acquisitions team, we created a form to invite collection creators to share information about their identities. In the future, we will ask creators to provide information about the terms they use to describe themselves.

Unfortunately, this won't solve our problem with old finding aids that describe collection creators who are no longer living. Still, we can do our best to use accurate, non-pejorative, and up-to-date terms. There are many wonderful resources for this, published by people who represent many identities. This aspect of our Guidelines is addressed in the Identity & Naming section.

We also focused specifically on how to alter our practice for identifying creators' race. When the creator of a collection is white, past practice was to not mention their race; whiteness can be assumed, or at least it was not considered a notable part of the context of their life. But collection creators who were part of groups underrepresented in medicine were often described in racial terms. For example, in our finding aids, Black physician Louis Tompkins Wright had been described as a "Negro," while no white physicians were described as "white." In her paper on the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill’s “conscious editing” project, Jackie Dean describes her team’s goal to “reenvision our descriptive practice so that whiteness is no longer the presumed default […]." Following their lead, we agreed that it's valuable for us to name whiteness in our finding aids going forward. Whiteness is indeed the "presumed default" in medicine. Perpetuating that in archival description only serves to obscure the role of white privilege in the medical field.

In the end, our new guidelines read, in part:

“When you know the collection creator’s race or ethnicity, identify them by their race or ethnicity in the Biographical Note. […] Describe the collection creator’s race or ethnicity using terms described in primary sources, such as records from the collection, census records, or other documents from the creator’s lifetime. Cite the source, either in the text or using a footnote. [...] If the person’s race is described in secondary sources (biographies, articles, contemporary sources), use this term, providing a citation."

So how did we do that? To avoid making assumptions about people's race, we looked to census records. Here’s an example. The finding aid to the Ernest Amory Codman papers now includes the information that “Codman was identified as white in the 1930 U.S. Census.” We also added context to the original description of the Codmans as a "Boston Brahmin" family. These identifications serve as reminders of the advantages afforded by whiteness, maleness, and/or wealth. Black people, women, and others were systematically denied these same advantages for centuries.

In the case of the Jacob Moreno papers, we updated the finding aid to read: "[Moreno] was identified as white in the 1930 U.S. Census, and he self-identified as Hebrew in his 1933 U.S. Petition for Citizenship." Describing Moreno's white and Hebrew identities provides context for his life experiences and career, first in Austria and then in the United States.

The previous version of the Louis Tompkins Wright papers finding aid, in which Wright was described as "Negro," was what we call a "legacy" finding aid. This means that it was written long before our current standards of archival description were in place, likely in the late 1980s. In our updates to the Louis Tompkins Wright finding aid, we removed the outdated term "Negro" and described Wright as Black. We kept a 1938 magazine quotation from the original finding aid that described him in as "the most eminent Negro doctor in the United States." A researcher will see the terms used for and by Wright during his lifetime, as well as the term that most Black Americans use today.

We hope that these descriptive guidelines will help us to achieve our goals: describing collection creators with respect and being transparent about race. We invite your feedback via email.