The volume of paper and digital records produced by humans in the course of their lives and work is unfathomable. What ends up preserved in archival repositories is at best a “sliver of a sliver of a sliver,” in the words of Verne Harris (1). The records in our collections represent the work of people who contributed to medical discovery and innovation, particularly people with connections to Harvard; here, as in most American archival institutions, Black people and women are underrepresented, something we are working to change. In her 2018 Tedx talk, Dominique Luster, the Teenie Harris Archivist at the Carnegie Museum of Art, posed some critical questions about archival silences: “Whose letters will I never find?” she asked. “If your history isn’t recorded and preserved, well, did you exist?” (2) These questions were in our minds when a researcher at the Center for the History of Medicine asked us about someone named Myra Logan. Would we find her records? Did she exist?

Myra Logan was a Black woman and the first woman to perform open heart surgery. Her records were not preserved together in an archive and made accessible to the public. However, though Logan is not represented in her own right, we were able to find her mark in other people’s archives. The traces of Logan in the Center’s Louis Tompkins Wright papers made us interested in learning more about her very remarkable existence.

Myra Logan was born in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1908 to Warren and Adella Logan. Warren, who had been formerly enslaved, was the treasurer of the Tuskegee Institute, while Adella was an educator and a strong advocate for women’s suffrage. Logan received her bachelor’s degree from Atlanta University and a master’s in psychology from Columbia University. She furthered her studies at New York Medical College, where she was the first student to receive the Dr. Walter Gray Crump Scholarship. This $10,000 scholarship was created to aid Black students who wanted to pursue medicine. Logan graduated in 1933 and then completed her internship and residency at Harlem Hospital, where she was only the second woman intern. She then became an associate surgeon at the hospital. In 1943, Logan was the first women to perform open heart surgery and was the first Black woman to be elected to the American College of Surgeons.

Besides her clinical achievements, Logan was a civil rights activist. She was a member of the Planned Parenthood Association, the National Medical Association Committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the New York State Fair Employment Practices Committee. She served on the New York State Committee on Discrimination until 1944, when she resigned in protest after Governor Thomas E. Dewey denied antidiscrimination legislation.

While working at Harlem Hospital, Logan crossed paths with Louis Tompkins Wright, where the pair collaborated on clinical research with Aureomycin, an antibiotic they used to treat lymphogranuloma venereum (3). Their careers in medicine had similar origins. Both grew up in Georgia as the children of formerly enslaved fathers who later achieved professional success. (Logan’s father became Treasurer of the Tuskegee Institute, while Wright’s father graduated from Meharry Medical School and became a minister). Like Logan after him, Wright went north to earn a medical degree, in his case, from Harvard Medical School in 1915. He experienced racial discrimination throughout his education and career in medicine, and he advocated for himself to receive the same training opportunities as his white peers. Upon joining the Harlem Hospital staff in 1919, Wright became the first Black medical staff member at a New York municipal hospital. He also led as a surgeon, researcher, and mentor for Black medical residents. As NAACP president, he worked against hospital segregation and promoted opportunities for Black medical trainees and patients (4).

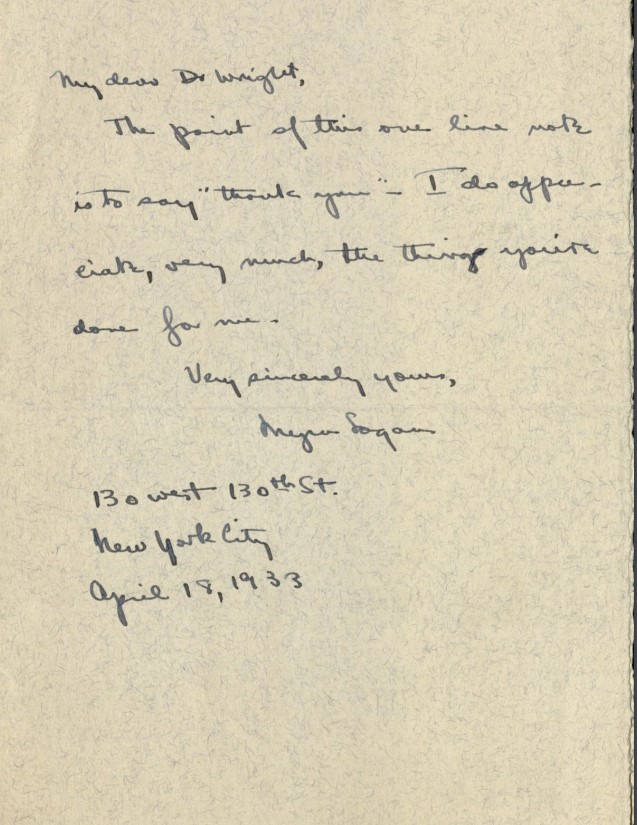

Records indicating Logan’s colleagueship with Wright appear in the Louis Tompkins Wright papers. A photograph shows Logan and Wright together at the bedside of a patient; a letter from Logan to Wright explains Logan’s decision to delay her application to a meeting of the Harlem Medical Board. Logan also writes to Wright to thank him for some unspecified kindness: “My dear Dr. Wright, The point of this one line note is to say ”thank you”--I do appreciate, very much, the things you’ve done for me. Very sincerely yours, Myra Logan.” Similarly, Logan’s brother, physician Arthur Logan, writes to Wright, expressing “appreciation […] for your interest and guidance during the past months. I have learned, I believe, much from you – some surgery – but what is more important by far, I think that I grasped a bit of your uncompromising demand for integrity of thought and action in all things.”

These items from the Wright collection teach us a little bit about Logan’s relationship with Wright. The New York Times and New York Medical College have written to offer additional information about Logan’s life and accomplishments. However, no publicly available collection of Logan’s personal and professional records exists, as it does for Wright. In the archives, Logan only exists in relation to the prominent men around her: in fragments of the Wright papers, and in the papers of her husband, artist Charles Henry Alston, at the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian. No archival organization collected the Myra Logan papers (whether any tried, we do not know), and so the robust record of her work and achievements does not exist for researchers from the public to consult.

Archival scholars have studied how archival practices obscure the legacies of individuals who may not have been in the limelight or who labored under more visible people. Rodney Carter writes: “The power to exclude is a fundamental aspect of the archive. Inevitably, there are distortions, omissions, erasures, and silences in the archive. Not every story is told” (5). These silences tend to leave out Black people, women, and other members of historically marginalized groups. Often, people like Myra Logan are only discoverable through more prominent men they had professional and personal relationships with—In Logan’s case, Wright and Alston. It’s likely that records about Logan exist, either scattered in other archival collections or held privately. By drawing attention to her through her small place in the Wright papers, we shine some light on her extraordinary life and career and recognize her absence from the archive.

Read “Women in Medicine Are Proving the Exception” in The New York Age, by Myra Logan (October 29, 1949).

- Harris, Verne. “The archival sliver: Power, memory, and archives in South Africa,” Archival Science 2, (2002), 63–86.

- Luster, Dominique. (June 2018). Archives Have the Power to Boost Marginalized Voices.

- “New Potent Antibiotic.” Science News Letter 54, no. 5 (July 31, 1948): 69.

- Reynolds, Preston P. “Dr Louis T. Wright and the NAACP: Pioneers in Hospital Racial Integration,” American Journal of Public Health 90, 6 (June 2000).

- Carter, Rodney G.S. 2006. “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence,” Archivaria: 61 (September), 215-233.