The History of Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Did you know that Brigham and Women’s Hospital was created by the merger last century of four famous Boston institutions? The legacy of these four, whose combined history dates back to 1832, is reflected in the name—Brigham, for the Peter Bent Brigham and the Robert B. Brigham Hospitals—and Women’s for two women’s hospitals, the Boston Lying-in and the Free Hospital for Women (collectively known since 1966 as the Boston Hospital for Women).

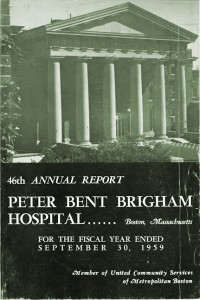

The BWH Medical Library and Archives has sponsored the digitization and posted online complete runs of the annual reports for two of these venerable ancestors, the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital (1913–1979) and the Free Hospital for Women (1875–1965) which represent some of the richest resources available, not only for information on BWH history, but also on the evolution of medicine as practiced at hospitals. (The reports for the Boston Lying-in Hospital (1875–1965) will be available online later this year.)

Gone Fishing

If you can’t imagine yourself reading any annual report if you didn’t have to, you might change your mind for these. The presentation of information about the financial and professional activities of organizations in the 19th and 20th centuries was very different from that which we are familiar with in the 21st. Not the same thing at all. Since modern company reports also serve a marketing and publicity function, the resulting publication can sometimes have the flavor of a hyperbole sandwich with a dry statistical filling. Presented with a graphically sophisticated brand identity and an abridged writing style, modern annual reports are designed for an Internet-connected world which reflects the probability of reaching, not only its board of trustees and investors, but also a largely unknowable, skim-and-click audience.

A 20th century version, however, could include anything from a monologue on the dangers of complacency in the post-war hospital to a friendly story about a doctor’s fishing trip to Newfoundland.

At the old Peter Bent Brigham Hospital these yearly communications were written in narrative style and reflected the unscrubbed musings of the department head tasked with making the report. Along with the expected statistics on admissions and treatments, notes on staff, department activity highlights, research objectives planned and met, and publications, the hospital department heads, having a reasonable expectation of a limited audience for their words, often included anecdotes, editorial commentary on hospital policy, the history of their field, or the advancements in medical science as they were realized.

You can follow the footprints of many steps in the march towards modern medicine in these reports. The Peter Bent Brigham Hospital was in the vanguard of successful experimentation in heart surgery, the rise of neurosurgery as a specialty, the development of the “iron lung,” kidney dialysis, organ transplantation, antibiotics, and the professionalization of nursing. The Free Hospital for Women produced some of the most important advancements in medical science related to women’s health. You can also learn the effects on the staffs and the practice of medicine due to crises—local and global—such as epidemics, disasters, and war. For those of us interested in the lineage of the big and small ideas that became professional doctrine, a trip through the old-style hospital reports will be illuminating.

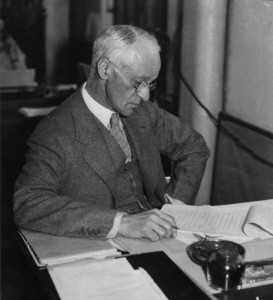

For example: One of PBBH’s most famous alums, neurosurgeon, Dr. Harvey Cushing, applied his graphomania (archivist’s diagnosis) to his surgeon-in-chief reports up until his retirement in 1931. Dr. C recorded the evolving organization of the new hospital’s surgery division. He spent 9 pages of his 1920 report discussing the success of the Brigham’s implementation of the new “residential system” introduced to American teaching hospitals by Dr. William Osler at Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1890s, and the Brigham’s own novel adaptation to the Hopkins model—the “full-time service” idea. This idea allowed chiefs-of-service, assistant physicians and surgeons to have offices at the hospital in order to devote their undivided attention to it, rather than having more than one place of business. Imagine that.

Barrel of Apples

The Free Hospital for Women Annual Reports carry us back even further, to a time—flip-flopped from our 21st century experience—when hospitals were created by those whose higher social class expected at-home medical care, for those so poor their only option was to be treated at a hospital. In 1875, the Free Hospital for Women (and it really was free!) was opened with 5 beds “for poor women affected with diseases peculiar to their sex or in need of surgical aid” by a volunteer triumvirate of socially conscious medical men, church men, and well-to-do ladies.

The earliest FHW annual reports reveal just how dependent health care was on the “kindness of strangers” in the 19th century. Sponsor a bed for $150 (about $3300 in today’s money) and you got a seat on the governing board plus the option to decide who could be admitted as a patient to that bed. A substantial donation to the hospital got you your name listed in the annual report, similar to our contemporary custom, however, the definition of “substantial” has certainly evolved over the past century. The 1876 donor list reports contributions such as a “demijohn of whiskey”, “a barrel of apples,” “one ton of coal,” “a hair mattress,” — the lists are charmingly detailed. Donation reports of this nature were included in FHW annual reports through the 1930s.

Filling a desperately needed niche, the Free Hospital for Women saw the rapid growth of the size of its physical plant along with its role in women’s health research. Its yearly reports offer the curious a chance to devour a banquet of data on the genesis and progression of ideas in women’s health. Just to mention a few, the FHW led in the adoption of antisepsis techniques in hospitals, opened the earliest cancer wards, achieved in-vitro fertilization, and created the birth control pill. Not bad for a place that started with 5 beds and a barrel of apples.

These type of narrative yearly reports ended at the Brigham in the early 1980s, soon after its four parent hospitals moved in together under one roof. The pace and complexity of such a large institution likely made continuing the more personal style of reports impossible.

The reports are freely available and searchable online via the above links or through the Harvard HOLLIS Library catalog.

Free Hospital for Women Annual Reports

Peter Bent Brigham Hospital Annual Reports

This news post was originally published on the Center for the History of Medicine’s Wordpress site.